Design Methodology - How it all started

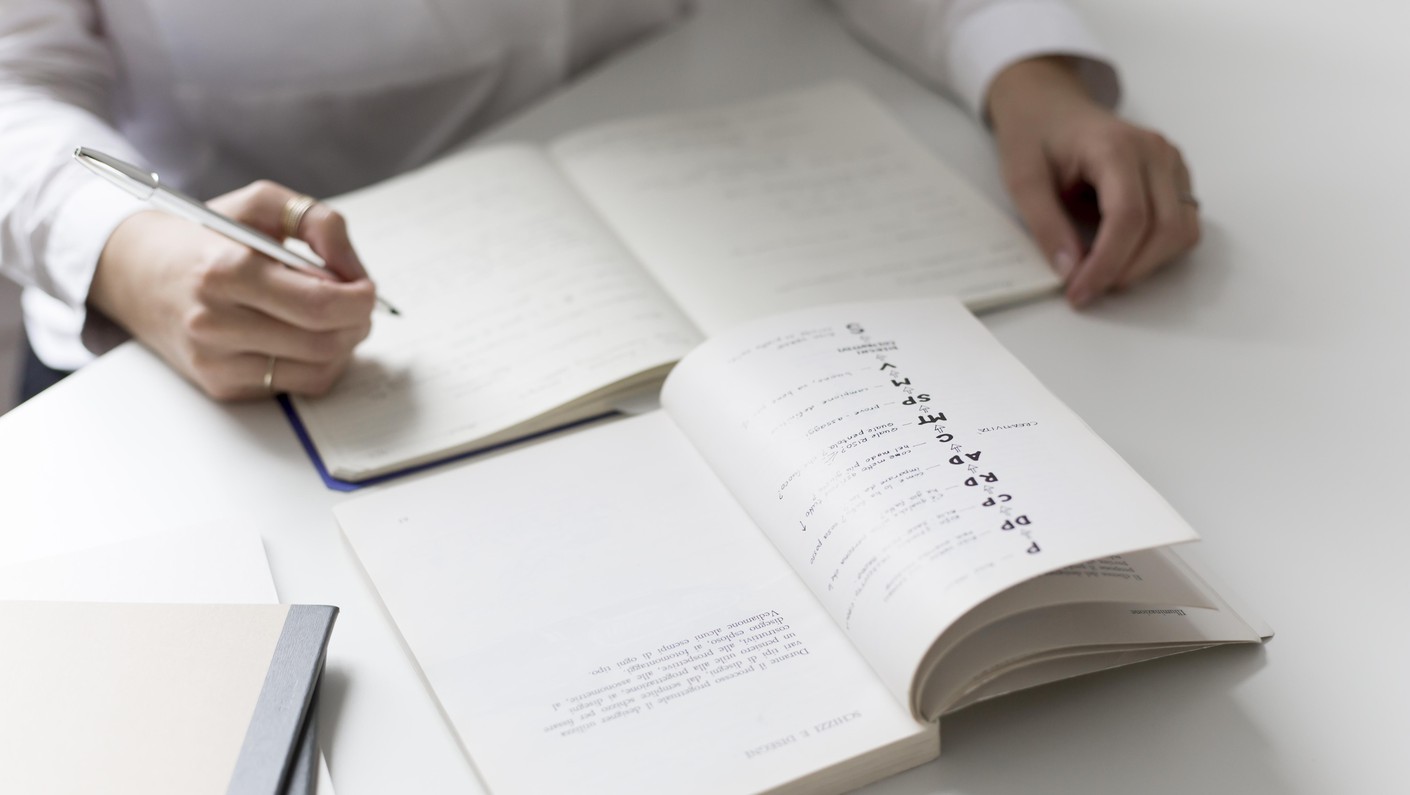

For my first contribution to this blog I decided to go back to the beginning of all this. I’m not talking about the beginning of our wonderful studio :) but the beginning of my fascination with design.

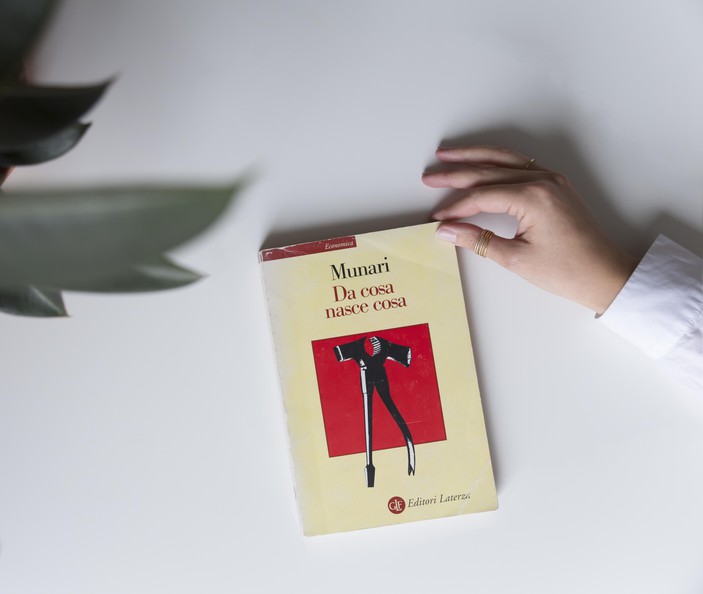

It was 1999 and I had just started university. A friend called Pietro gifted me a book that was destined to deeply influence my life: Bruno Munari’s “Da Cosa Nasce Cosa” or “Out of One Thing Comes Another”. Unfortunately this book is not translated into English, so this is my small attempt to share some of Munari’s wisdom with the English speaking world.

Mr. Munari (1907-1998) believed that creativity was within everyone’s reach when given a methodology to follow. He believed that everyone could design, everyone could be ‘creative’, when provided with the right tools . In his book, he illustrates his design methodology step by step, which is a wonderful starting point for people learning about Design, Design Thinking or maybe just have a problem to solve creatively.

Our proprietary method has its roots in Munari’s method, but it has evolved over the years working on design projects. I’ll explain how.

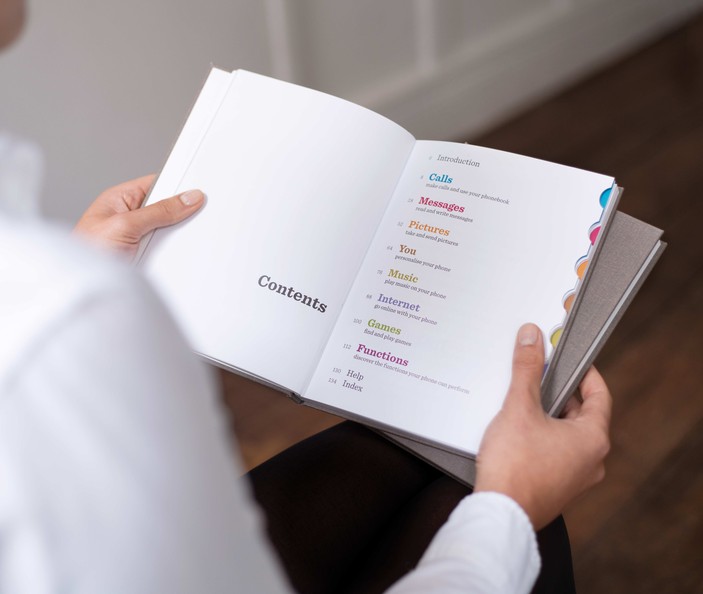

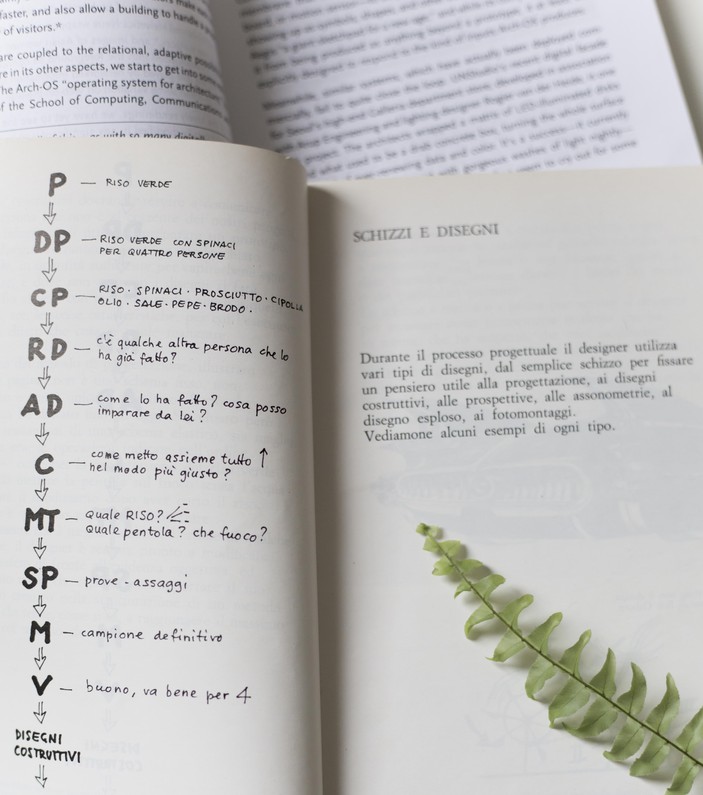

Munari’s method goes like this:

1. Problem

2. Problem Definition

3. Problem Components

4. Investigation/Data collection

5. Investigation Rationalisation/Data analysis

6. Creativity

7. Materials & Technologies

8. Experimentation

9. Prototyping

10. Testing

11. Techical drawings

12. Solution

This process can be applied to any problem, large or small. From planning the interior of a new home, to creating the latest cutting edge app. Let me walk you through this.

1. Problem

A problem is the start of many projects. It can be a functional or ergonomic problem, or even an emotional one. You might want to enable people to access a difficult piece of tech, or design a less stigmatising blood pressure monitor, or a more polite bathroom scale, for example. At Special Projects we call this phase Opportunity, to open its realm up beyond problems. For example, an opportunity can be a new technology becoming available, and this would make a great project starting point.

2. Problem Definition

This is, in my opinion, the key part of a project. This is the moment in which the designer needs to take a step back and define the problem, refraining from proposing or thinking about solutions. This is hard but it is worth it. B. Archer in his ‘Systematic Method for Designers’ says “Many designers believe that the problem is sufficiently defined by their clients. But this is largely insufficient.” We believe in working with our clients to define the perfect Opportunity, often opening up the brief to allow space for more effective (and unexpected) solutions.

3. Problem Components

Munari here suggests ‘disassembling’ the problem into its component parts. Sectioning the problem into smaller problems allows them to be solved more easily. This is inspired by the second rule of the Cartesian method of “dividing each problem into many minor parts, until it is easy to solve". This process is increasingly relevant as products become more complicated, spanning the digital and physical, as many of our projects do. Every small problem has its optimal solution that contrasts with others. The skill of the designer is the ability to reconcile each solution to the overall project.

It was 1999 and I had just started university. A friend called Pietro gifted me a book that was destined to deeply influence my life: Bruno Munari’s “Da Cosa Nasce Cosa” or “Out of One Thing Comes Another”. Unfortunately this book is not translated into English, so this is my small attempt to share some of Munari’s wisdom with the English speaking world.

Mr. Munari (1907-1998) believed that creativity was within everyone’s reach when given a methodology to follow. He believed that everyone could design, everyone could be ‘creative’, when provided with the right tools . In his book, he illustrates his design methodology step by step, which is a wonderful starting point for people learning about Design, Design Thinking or maybe just have a problem to solve creatively.

Our proprietary method has its roots in Munari’s method, but it has evolved over the years working on design projects. I’ll explain how.

Munari’s method goes like this:

2. Problem Definition

3. Problem Components

4. Investigation/Data collection

5. Investigation Rationalisation/Data analysis

6. Creativity

7. Materials & Technologies

8. Experimentation

9. Prototyping

10. Testing

11. Techical drawings

12. Solution

This process can be applied to any problem, large or small. From planning the interior of a new home, to creating the latest cutting edge app. Let me walk you through this.

A problem is the start of many projects. It can be a functional or ergonomic problem, or even an emotional one. You might want to enable people to access a difficult piece of tech, or design a less stigmatising blood pressure monitor, or a more polite bathroom scale, for example. At Special Projects we call this phase Opportunity, to open its realm up beyond problems. For example, an opportunity can be a new technology becoming available, and this would make a great project starting point.

This is, in my opinion, the key part of a project. This is the moment in which the designer needs to take a step back and define the problem, refraining from proposing or thinking about solutions. This is hard but it is worth it. B. Archer in his ‘Systematic Method for Designers’ says “Many designers believe that the problem is sufficiently defined by their clients. But this is largely insufficient.” We believe in working with our clients to define the perfect Opportunity, often opening up the brief to allow space for more effective (and unexpected) solutions.

Munari here suggests ‘disassembling’ the problem into its component parts. Sectioning the problem into smaller problems allows them to be solved more easily. This is inspired by the second rule of the Cartesian method of “dividing each problem into many minor parts, until it is easy to solve". This process is increasingly relevant as products become more complicated, spanning the digital and physical, as many of our projects do. Every small problem has its optimal solution that contrasts with others. The skill of the designer is the ability to reconcile each solution to the overall project.

Here Munari suggests investigating the market, the competitors, the components and the existing solutions. Although this is very important, I find Munari’s approach most appropriate for projects which require only an incremental improvement of an existing object, rather than a truly innovative project where a new product or service is invented, in which case the research should span many more ‘lateral’ topics, such as parallel markets, product ecosystems, new trends etc. In addition, to avoid being single minded about a product, we believe in involving a group of different users during this early stage of the project to act as ‘muses’ and fill us with inspiration. :) So rather than Data Gathering, I would suggest doing a deeper, more meaningful 360 degree investigation.

This step requires the designer to take a step back and analyse all the data collected. We call this Distillation of Insights. An insight is something unexpected that you have learned during the Investigation Phase and can shape the whole project direction. Insights often answer the following questions: What is best practice in solving a similar problem? What is the most recurrent problem or aspiration expressed by the users? What has been overlooked by the industry so far?

Munari uses the word creativity, and not ‘idea’ to express that the designer will propose a solution that takes into account the technical/rational aspects of a project, and avoid proposing only ‘ideas’, which may not be grounded in reality. We like to take on-board not only the technical constrains of a project but also the emotional experience of the user, aiming to create the fuzzy feeling of delight that we often borrow from the magic world.

Once a creative solution has been proposed, Munari suggests thinking about the most appropriate materials and manufacturing technologies to use.

Experimentation is paramount when choosing the best material and technology for a solution, and the designer should experiment with existing and traditional materials but also venture into creating innovative materials or techniques.

Samples and prototypes are created as an outcome of experimentation, and the solution is refined each time.

This is the time to present the most appealing prototypes to some users. In the industry this is now called Validation Testing. We love this bit, and we use magic techniques to keep prototyping costs down. We create a wonderful environment to transport users into the new concept we have created. Keeping a poker face and welcoming all feedback, negative and positive, is key to creating meaningful innovation. Filming the session is very useful to refer back to users reactions. Designers will need to move fluidly between steps 7 and 10 to reach the perfect design solution.

At this point Munari explains that designers will have to ‘translate’ the design into technical drawings for the manufacturer. We communicate the product vision to our clients in many ways, from technical drawings and looks-like prototypes, to videos showing user interactions. If the product has a digital element, wireframes and app mock-ups are produced.

The solution is then presented and communicated to all stakeholders.

We believe that Munari’s attitude towards creativity is inspirational, and effective. So fear not and tackle your design problems or new opportunities with method and discipline, and you will be impressed by the results!

Beauty is the consequence of right doing.

Japanese saying

Il bello è la conseguenza del giusto.

Detto giapponese